Can you estimate without knowing the solution?

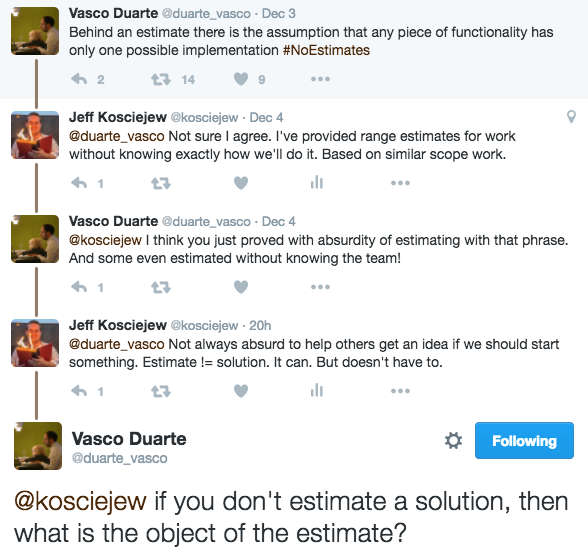

Recently, on Twitter, a post came across my feed. I responded to it. Which generated a response. Which I really couldn’t figure out how to respond to in 140 characters or less.

The thread is on the right…

And, below is my (slightly longer than 140 character) response:

First of all, let me be clear that I’m talking about work in the obvious or complicated domains. I’m not talking about something in the chaotic or complex domain. If this doesn’t make sense to you, have a look at this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N7oz366X0-8

And why is this important? Well, because in the obvious or complicated domains, it’s something we’ve done before. Maybe not you, specifically. But someone has.

Building a 747 is a solved problem. We know how to do it. Well, not me. I don’t have a clue. But there are experts I could go an ask, and since they’ve done it, they can help me. There might be different ways to build it, do things in a different order (again, I have no idea), whatever – not the point. My point is that if someone were to ask me to build a 747, I could provide them with an estimate to do that, without knowing exactly how I was going to do it, by talking to the experts who have done it before, and solved that particular problem.

Let me get out of 747’s, and into a domain where I have a little more experience…

A few years ago, I was asked to provide a quote to a potential customer on the cost to build a web application, with specific functionality and usability requirements. And to be clear, I had never build this specific web application before. But, I had been part of teams that had built other web applications, with similar functionality. So I could apply expert judgement, and validate some of the assumptions I made with others on the team who had also built similar solutions for other clients. And we did. We ended up with an estimate for time and cost, and we wrote the SOW with enough latitude that we could adjust the specifics of the scope along the way. Not for our benefit, although it did work out well for us. But really for the benefit of our potential customer.

You see, we’d built similar applications in the past. We had an idea that what the customer was asking for wouldn’t actually be what they wanted once we got started. And we were right. It was on day three of the project when the customer changed their mind on something, and wanted an additional section to be added. No problem. We weren’t contractually obligated to deliver on any specific item. What we were on the hook for was to deliver a web app to help them solve a business problem.

And when the customer asked for changes, on day three, we were able to have a meaningful conversation of what that might mean to the overall project, and allowed us to look at ways of providing a better solution to solve their problem, and meet their needs. We spent a lot of time over the course of the project, working directly with the customer to build something that would work for them. We re-architected aspects, change the information architecture, created an enhanced UI, and made their initial UX designs far superior & easier to navigate and use. None of this was scoped explicitly at the outset. But we still provided the potential client an estimate.

Our estimate, which fed into the budget and allowed us to earn their business was a key in this process. It provided a budget for the customer to decide if they wanted to start the project at that time, or hold off until a later date. We didn’t need a specific solution. We just needed to be 80% confident that we could deliver something that would solve their problem, in the time they wanted it, for a price they could afford. And yes, we told them that our estimate was likely off a bit, but that we were willing to assume the risk through a fixed price contract. Remember, we’d done very similar work before. We were clearly in the complicated domain for our team.

There was a huge industry convention coming up for them, and they wanted to feature their new web app at that convention, if they could.

So, estimating a solution depends on how you define the word solution. Going back to the initial tweet, that “behind an estimate there is the assumption that any piece of functionality has only one possible implementation”, is flawed if you mean defining how, specifically, we’re going to solve the problem.

Providing an estimate, in this context, as to what problem we’re going to solve, actually frees the team to come up with any solution they can imagine, while providing a constraint that something needs to be done by a certain date. And, that it’s all based in actual historical data, so it’s not just a wild-ass guess. An estimate doesn’t need to be based in a single solution, and thinking it does constrains the learning and ongoing conversations that can and should occur during the development. I’d suggest that if this isn’t the case, you might be doing it wrong.

I’m a huge proponent of #NoEstimates. I believe there are lots of better ways to make decisions, and make shared, informed choices about how we spend our money. I also believe that not everyone is on that same page. And that, in certain contexts – like this one – an estimate can be a good thing. Without that estimate, our potential customer would never have become our actual customer. No one wins in that scenario. By providing a simple estimate in this case, we were able to earn the business, and deliver an exceptional product about 20% under budget and 22% ahead of time. Oh, and as a fixed-price contract, that went directly to our bottom line. Happy customer. Happy business. Happy team.

When we’re in the complex or chaotic domains, I think you’ll have a tough time convincing me of the value of most estimates. But when it’s a solved problem – something we know how to do – an estimate can not only be quite accurate, it can be quite helpful. We need to be aware that sometimes, when we think we’re in the obvious or complicated domains, we’re not actually in the complex or chaotic domains. It’s often tough to tell. And, I’m not content with the status-quo, so I’m always going to be looking for ways to challenge anyone who says “well that’s how we do it here”. In this case, I’m pretty happy with the choices we made, the estimate we provided, and the result we delivered.

We need to be careful with absolutes. There can be a time and place for anything and everything. We should continue to question everything in order to continue our quest to find better ways of working together, making decisions, and solving problems.

Communities of Practice

I've been asked by a few people if I have any information on starting and maintaining a Community of Practice.

It's taken me longer than I would have liked, but I finally have compiled some information, with thanks to Ellen Grove and Tyler Motherwell (and Wikipedia , too), for lending their support. I hope you find some of this helpful, and will share what, if anything, you've found helpful or have tried yourself to help others. With their assistance, I've actually found material better than what I had to share anyway. So hopefully you find this useful, if you're interested in setting up and maintaining a Community of Practice.

That, by the way, is at the heart of a Community of Practice (or CoP). Helping others, and finding ways to improve ourselves.

Communities of Practice extend beyond what team you're in. CoP's are best when they're an amalgamation of people from different teams, with different experiences, but aligned with a common purpose. As we think about building cross-functional team in order to provide teams with the skills and expertise to get work done quickly and effortlessly, we're likely going to find that teams will be comprised of various job families, each with their own skill-set.

Let's just say I happen to be a Data Scientist (for example) - if I'm not working on a team with other Data Scientists, I may not learn and grow in my area of expertise on a daily basis. Since my team might be comprised of BAs, Designers, and Product Managers, I'll gain an appreciation for those roles... But I want to continue to improve my skills as a Data Scientist. This is a perfect place to introduce a Community of Practice.

Quite simply, a Community of Practice is a group of people who share a common craft/profession, have a passion for what it is that they do, and want to learn how to do it better through regular interactions. So how do we make this happen?

A couple years ago, Mitchell H. "Mitch" Ruebush wrote a nice intro to ways to start a CoP. He's got some key steps outlined in the appropriately named Starting a Community of Practice post. Some key thoughts to consider when setting up a Community of Practice (kindly provided by Tyler):

Objectives:

Provide a safe forum which - above all - serves to disseminate knowledge about the subject the members gather to discuss

Anyone can attend

All members have an equal right to participate

Subjects & Topics:

The overarching subject of the CoP can be any shared interest, and as broad or as specific as the members want it to be

Meeting-specific subjects can be selected one meeting in advance through participants’ voting

The Facilitator can be responsible for proposing a list of subjects for the upcoming meeting, and any participant can add to the list

Members & Roles:

CoP participation should be voluntary. Meetings can be open to anyone across segments, functions, and levels, or restrictions can limit participation to certain groups

Participation is not driven by enforcement, but by staying relevant to core participants

Two voluntary roles are recommended: a Segment CoP Champion and a Facilitator

The CoP Champion raises CoP awareness within the segment, organizes the first meeting, and provides/receives input and feedback

A Facilitator organizes subsequent meetings and facilitates the sessions. Role rotation can be every month or two

Agenda:

If CoP selects subjects in advance, subject selected in previous session

Moderated discussions of recent experiences, impediments, and learnings

Status updates are not part of a CoP meeting

Frequency & Duration:

Cadence and duration are at the discretion of the CoP’s core participants

Normally, CoP meeting duration is between 30 and 60 minutes, with cadence varying anywhere from weekly to every two months

As a suggested starting point, try to set the CoP meeting cadence to be weekly. And then adjust as applicable to the group

Communications:

Communications developed by the Facilitator. Channels can extend beyond email

SharePoint or a wiki can be used if members will be sharing documents frequently

Communications are internal to the members. External communication happens on an ad hoc basis

Internal communications include meeting highlights, sharing of material used during presentations, and any other internal CoP announcements

Some fantastic ideas to consider in that list, for sure.

And, if you've made it this far in this post, I'm hoping you're looking for more. Have a look at these:

https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

https://www.wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/13-11-25-Leadership-groups-V2.pdf

I was going to extract bits from these documents, but I think they're worth reading and having in their entirety. I hope you'll also find them useful.

The first one, titled a Brief Introduction to Communities of Practice provides an intro to CoP's. And while it claims to be an "intro", it has a wealth of information and includes suggestions for further reading.

And the second one, titled Leadership Groups - Distributed Leadership in a Social Setting , is really designed for CoP "facilitators, conveners, or coordinators who want to develop the social learning capability of a community of practice or other type of learnin partnership." This is an exceptional read, with great ideas to consider.

Hopefully some of this is helpful. It certainly was helpful to me when starting and sustaining CoPs in various places I’ve had the opportunity to work. Good luck!

What’s Wrong with ‘Best Practices’?

There’s a problem with best practices.

Don’t believe me? If you’ll take a few minutes to read this post, I hope to convince you I’m right. And, more importantly, get you to think about problem solving a bit differently.

But let me start here: A best practice is the best. It can’t get better. It already is the best. We don’t have bestest practices. Once we have a best practice, we’re done.

In almost every industry, and in every line of business, having a best practice would make our lives easier. If there really is a best practice, why don’t all companies do whatever that best practice is? Maybe it’s because there isn’t one best way to do everything. Maybe it’s because what’s a best practice in one company, isn’t going to work in another. Maybe there are cultural differences in the companies, or lines of business.

I believe best practices are a cop-out. I believe they’re a lazy way to decide what to do. They’re a way to solve a problem, or exploit an opportunity, that someone else has decided on a solution that worked for them. And it may or may not work in this new situation. But we adopt it without understanding why. We adopt it because someone decided it was a best practice.

It’s way harder to dive into understanding a problem, getting to the root of the issue, and then researching multiple approaches for solving it. Or, using the wisdom of the teams directly involved with that area of the business. Or leveraging what others have done in similar circumstances to come up with our own hypothesis, which can be tested and validated. It’s much easier to simply implement something because someone else did it in a situation that looks similar to ours.

What’s worse is when we do something because it’s an “industry best practice”. How does a person, team, line of business, or company differentiate itself from another, if it’s simply adopting things that have already been done by others? In today’s world, for something to be considered a best practice, it has to have been done, and work, somewhere else. But isn’t there a problem with wanting to be the best at something, or the number-one something, when, by definition, you’re copying someone else’s approach?

In the 2004, a British newspaper, The Independent , switched it’s paper format from broadsheets to tabloid format. For over 400 years, in order to be considered in the industry a quality and respected newspaper, you printed on broadsheet sized paper. This was an industry best practice, well established, and unquestioned. So in 2004, when they switched their format to the tabloid size, you can imagine the industry’s surprise when they saw a circulation boost. And other papers followed, also seeing circulation surges.

Our brains are wired to look for patterns and quickly find solutions.

Sometimes, when we’ve found what we believe is a best practice, what we’ve really found is something that helps us view our complicated, complex, and often chaotic world. But it’s often an overly simplified perspective.

I worked for a company in my career, a company who will remain nameless. This other company has a SOP – their Standard Operating Platform. Effectively, this is their best practices, and is used for managing their business today. I was part of a team at this company that was trying to help the company expand into new, customer focused solutions. Instead of providing individual products, from different silos in the organization, they wanted to bring products from different areas of the business together, which would make sense for a specific customer demographic.

Seems like a good business idea – increase the number of products and services, in a single location, so customers could see that the products, while good on their own, could even be better when brought together.

But there was a problem. Each department, or line of business, wanted their products featured in their area. They didn’t want to include other departments products or services. That’s not how their bonuses were calculated, and it flew in the face of placing higher margin products in certain areas. They were focused on local optimization for their area.

Every time I tried to make a change, I was told by the silo’d departments and the marketing team that what I was doing was going against the SOP – this company’s best practices. The initiative failed because we couldn’t break through the current best practices of this company. They missed the opportunity to show their customers how the products & services they sold increased the value of each of the products individually.

Part of the problem is that there’s an assumption that if there was a better way of doing something, someone else would have thought of it.

What may have been a best practice for one company or industry may very well have been true. At that time. But rarely does someone do the work and research, expending effort to determine how long it remains a best practice. Or even if it is, in any other context.

One of the things that many companies talk about doing as part of their Agile journey, is measuring our team’s heath. Spotify did something that seems to have worked for them, and this was one resource I’ve provided in many companies. But, I always caution that this works for Spotify because it organically was developed, and as such, worked for them. Transplanting something from somewhere else may not work, even if it is a best practice elsewhere. What made it a best practice at Spotify is that it made sense for their teams, in their context, at that time.

By the way, if Apple had followed best practices, they would have released a six-button mouse, instead of the zero-button mouse. Whether you like or use the Apple Magic Mouse, the business result is that Apple doubled its market share overnight.

This doesn’t mean we can’t learn from others successes. And it doesn’t mean we can’t look at what others have done, and figure out how they’ll work for us. We absolutely need to look at what we’ve tried, as well as what others have tried. While we can’t, and shouldn’t accept that what’s worked elsewhere, or in the past, will work for us now, we would be remiss to not try to learn from existing knowledge.

And it also doesn’t mean there isn’t a place for a best practice. When the relationship between cause and effect is obvious, a best practice might make sense. For example, if I spill my glass of water, a best practice of getting & using a paper towel is a very applicable best practice. When my computer stops working, turning it off and then back on is a perfectly applicable best practice.

So, let me propose that we take what we think are our best practices, and call them our current practices.

The world is moving way to fast, and changing with such frequency that being complacent with thinking we’ve found the best practice won’t allow us to excel. Maybe we should simply think that we’ve found a current practice that works for us today, in our current context; one that we’ll need to continue to review and reevaluate on a regular basis.

In a complicated world, there may be many good practices to solve a problem. In a complex world, we may be looking for emergent practices.

Following best practices won’t make you the best. They make you the same as everyone else who follows them.